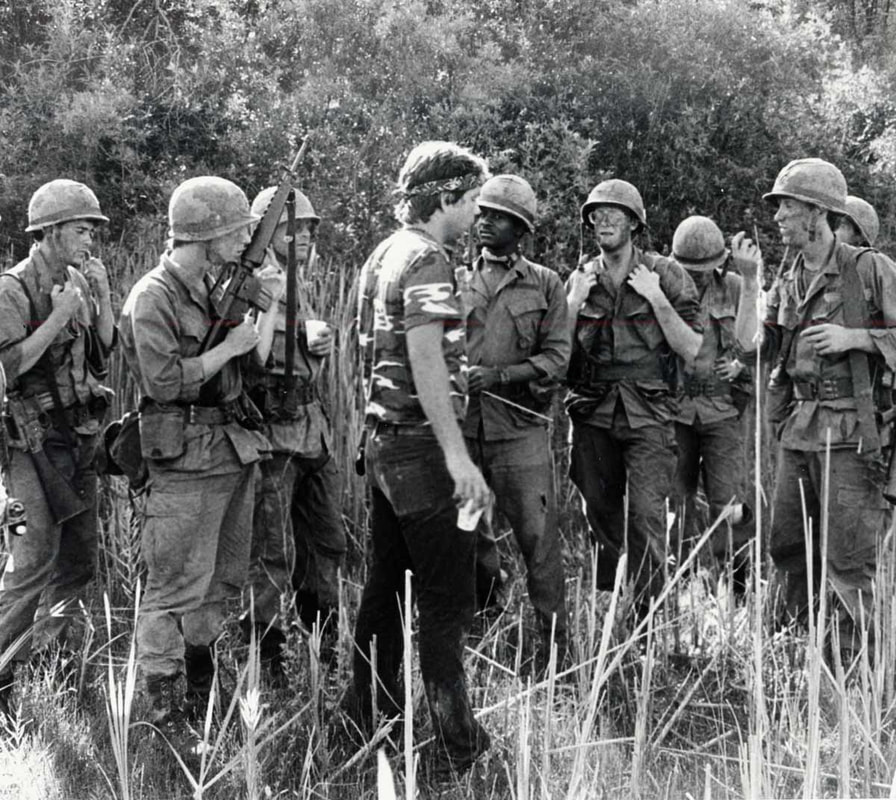

Cua Viet / June 1967

INTERVIEW: DANIEL REEVES by CHRIS MEIGH ANDREWS

C.M-A: How and when did you initially begin to work with video?

D.R: I went back to college under a veteran's rehabilitation program. I had been medivaced from the battle field, as it were, in January of 1968, and then had spent seven months in a military hospital and afterwards had about another year and a half to serve. During the last 6 months of my 4 year enlistment there was something called "project transition "which was notionally an effort to give combat veterans some other job skill, besides operating an M60 machine gun. In my case I was a field radio operator with a grunt platoon so it wasn't too far-fetched that I might study broadcasting. I was station at Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia and I opted to study at the National Academy of Broadcasting in my hometown, Washington D.C. not so far away. So I enrolled in the Academy studied radio and television there 40 hours a week during my last 6 months of my four year enlistment. This was my first contact with the Sony video portapak during the summer of 1969. The curriculum was designed to get you behind the desk as a radio announcer or TV personality, and that of course meant wearing a suit and being a slave to a schedule having just spent four years wearing a variety of suits that Thoreau would have mocked with gusto of one kind or another and trussed up in duty I got cold feet of the highest order, so I took my diploma and all those assertive and persuasive mouth skills that I had learned and just vanished into the countryside.

I lived in the woods in Maine in small cabin for about 3 years completely off the grid until I began to get restless. Then in 1973, I went to college under a disabled veterans rehabilitation program. This got me out of my "wounded retreat" brought on by shock of the combat, which was deeply traumatic, but my sense of betrayal had also forced a rupture with society that had undermined the foundations of my own metaphysical being. Somehow it was easy for me to link what was happening in the war to what was happening on the home front, or anywhere in the Western world in 1968 for that matter. What I perceived was that the war was about money and greed, xenophobia, racism all those things that were such deep and abiding flaws in our society. I felt poisoned by it all. So when I decided to re-emerge, I went to study journalism and early in my studies the great photographer & documentary film maker Willard Van Dyke showed up to run an intensive 3 month film workshop, which I attended with great enthusiasm. That summer was really a rebirth in so many ways as it became clear to me that working with a motion picture camera was somehow second nature to me. I had some previous experience - years before my stepfather had a 16 mm camera that was religiously hauled out for family rituals and events. The first film footage I recorded in my life, when I was 14 years old, was of a dam explosion, which seems kind of ironic looking back. My stepfather had contracted to build a six acre lake and the contractor and I spent days packing the dam core with dynamite resulting in a spectacular explosion which I filmed. So I began to study film, and my second contact with video was as a cinematography major. As part of the course you had to do one project in the TV studio. The problem was that it was very broadcast oriented, once again. So I did a short assignment- a camera podium piece where I worked with images from Northern Ireland- it was something that deeply interested me- I could never work on anything that I didn't interest me, even if it was an assignment. But because of the studio orientation and all the suits and clap-trap, I was still much more interested in film and still cameras than any work in what I might do in a neurotic and glamour addicted broadcast industry. After graduation I went away for 6 months to India, which was a very transformative experience on every level.

After returning, from India in January 1979, I got a position at Cornell University in the educational television department. I began to work with some film material which I had intended to use to make a reply to a film by Robert

Gardener entitled Dead Birds that he had made after taking part in an anthropological expedition in New Guinea. It was a project begun before I went to India, but that I had previously been unable to complete, as I simply could not resolve the structure and the ending. At Cornell ETV I had a kind of "Eureka" moment when I was able to sit down at the U-matic video editing system and learn the technical skills from my good friend and colleague Jon Hilton. I transferred all the film footage to video and it was precisely the plasticity, the spontaneity and the very smallish gap between inspiration and execution that was very engaging for me. I then transferred all of this imagery, 3 or 4 hours of film material that I had researched and selected from the National Archives in Washington.

That process of going back and digging deeply into archival footage wasn't a common practice at that point. I had never been able to make sense of this material even though it was what I had chosen myself. But when I transferred this material to Quad (2 inch video) I was able to modify the footage, change the contrast, add color, solarize and process shots in a completely new way for me. I created quite a few effects reels from the footage as well as the straight transfers. Jon and I made a decision to leave the sound out completely until the piece was edited. I could see and felt very strongly that the work that I wanted to make was about the sense of how the West particularly America, was always constantly balanced on the edge of nuclear suicide. As a society we didn't talk about it very much and rarely acknowledged it publicly except for certain notions about fall-out shelters and civil defense, and all the bizarre drills and schemes that came out later in wonderful pieces like Atomic Cafe.

So I ended up making a video work called Thousands Watch (1979). Its only 7 minutes long and effectively merges this footage from the 1957 Brussels World's Fair, film footage from Las Vegas and New York, archival war footage, and most importantly, black and white and color footage from Japanese film units at Hiroshima that had been confiscated and had only been released in 1975. These stunning film reels had sat locked away in a vault at the Army Film Archives for 30 years. The graphic horror of the event was very much a closely guarded state secret. So by transferring this material to video I was able to explore a new approach. Footage could be modified in real time and merged - at that time I wanted nothing to do with cuts. Cuts have rarely occurred in my work since then. I have, I suppose, an eternal notion of the fluidity that pervades the fabric of this world. But in the case of this piece, since it was only a 2 machine suite, and there was no time-base corrector or anything like that, the way I achieved the fluidity was by the simple creation of a black matrix which everything arose from, sustained, and subsided back into.

Thousands Watch piece was very successful, and was included in many festivals, which resulted in my being awarded my first NEA fellowship. After that I then went on to make Smothering Dreams. (1981). This was a real turning point because no one had made that kind of work dealing with that nuclear issues before. For me at that point, it became clear that the medium was going to allow me to make the work that I wanted to make. I think that within a month or two of making Thousands Watch I made a list of the works that I wanted to make, and all of them have been made. Obsessive Becoming (1995) is one of the last on that list, I think I then called it Seeds of Destruction.

C.M-A: Which aspects of the video medium do you consider to be the most important?

D.R: I became really enamored with and encouraged by the feeling that the video camera could be employed directly as a tool (within certain restrictions) in the same manner that a pen, or a brush or a carving tool is used. I had learned traditional art processes as well by this stage. Carving wood, and painting all of the doors and windows of my room, making sculptures with toy soldiers were early forays into art and some way of reaching for a catharsis, some means of being able to digest these violent experiences, or even being able to simply hold them in a real way. Discovering that I could now go out into the world with the camera, although it was still a relatively clumsy 3/4 inch U-matic recording deck. But clumsy or not, it went on a back-pack, and with the camera you could just capture things right there, and look at them instantly if you chose to. That relationship has now gone on for years, but to chart the changes over the years since then, I would look at the camera system first.

I had access to one inch in the field within a year or so, when Cornell got their first one inch type 'C ' machine. They were very generous when I was working on Smothering Dreams. I could rent a $48,000 'State of the Art' RCA 3 tube camera, with a Sony 'Type C' one inch portable recorder. So I had access to over $100,000 worth of equipment, renting for usually about $100 per day. I could take it home for the weekend, and work with the young actor who was in Smothering Dreams - just the two of us. The intimacy level is expansive, its very present. Setting up these shots with toy soldiers with 'Cherry Bombs' buried underneath them; I was trying to create a different landscape of the imagination - a dream world with the child looking at the soldier, and the soldier looking at the child.

So through the years, I would take notice every time there was a new technical development in field recording. For me this was not so much an issue of technical quality (although that interested me) but it was more that the camera became more and more of an extension of my own body. So whenever anything truly innovative came out in the marketplace, I would often be among the first to use these new systems. I had the first consumer level camcorder. It was a new format, brought out by JVC as VHS C. In the early 80's as soon as it was available, I went to "47th St. Photo" and bought the deck, the camera and this "marriage" device, which I used. I would wander for hours making what I called "ribbons"- I would move the camera, following for example, a battered tin pot (in a scene which shows up in Ganapati: Spirit in the Bush (1986) floating down the stream. Following the edges of tree forms, etc. You know- like having another eye in which you could pick up anything and everything.

From there it went to Video 8, High 8, SVHS. Every year or so changing my camera system. Now you can go out and buy a decent 3 chip digital camera for $1500. I went to India on a Guggenheim fellowship and I managed to convince Sony to sell me a BVP 110 and a BVP 50 at dealer cost, so I spent about $12,000 and I had a single tube broadcast quality set up to travel with. The whole configuration of camera and deck was designed for journalism and combat footage. I had never seen a camera that was so ergonomically designed (of course it’s a dinosaur now) It had a handle built into the top, an incredibly low profile, with a wonderful Fujinon zoom lens. The BVU 50, weighed about 15 pounds, it was 'record only'- you couldn't play back in the field, but by that time I was so conversant and familiar with the equipment and so confident that the footage would be there. I spent a whole lot of time traveling through France, Wales, Spain, and a few months in India before I saw a single frame of the footage. Much of the material from India was used in Sabda (1984).

So the technology has changed considerably. Right now I'm in a fallow period where I've made Obsessive Becoming which took 5 years to complete - the whole strange, alchemical process of putting that piece together. Since then I've made this piece called One With Everything (2000) which has practically been my undoing. I can understand why Woody Vasulka would say "I'm not sure that I believe in this single screen durational approach to working." I can't say that I've gone off it completely, but I came out of Obsessive Becoming with some sense of gratification. When I began to work on One With Everything, I decided to change my working method after being asked to deliver a finished work before a year was out. So I got 15 or 16 people together- the production values are very high. It was a disaster. Its been in lots of festivals, but I'm never happy with it. Like Woody I can look back and say "That doesn't work the way it should work".

Going back to what we were talking about...I'm at the point where I don't own a video camera. I've got enough distance from it now... You can travel around now with a shoe box containing all you need. You don't have to have that big suitcase full of equipment, but there's a trade off- because of the proliferation of digital effects, devices, potentials and possibilities within the camera and within the PC and Mac systems, etc., I would be completely bewildered if I was just starting out. It's as if you have to thread your way through this far too rich circus of delightful and complicated offerings just to begin the real work. I'm not saying this from a Luddite position, or that we should strip our cameras down and do pure black and white, but I sometimes go out and shoot something with Super 8 just because there's an aspect about it that is crude pristine and unpredictable.

C.M-A: Maybe its all got too controllable- too predictable.

D.R: To some extent. I'm a bit fed up with the learning curve. With Obsessive Becoming it wasn't five years in production - it was closer to ten years because I started in '85 with my first Amiga, and it wasn't till '93- almost '94 when I finally went "Aha!" This is the dream world that I wanted to get to. To be able to tear an image apart and re-form the image with complete freedom. Even though you are only working in two dimensions, its the apparent three dimensionality that matters.

C.M-A: Can you talk a little bit about your relationship to broadcast TV. What is the relationship between broadcast TV and your work?

D.R: I don't know whether I've come full circle or whether I've become completely jaded. Everything that I've ever made has ended up being broadcast in one form or another. Obsessive Becoming was picked up by "La Sept Arte". This was a tremendous boost in sales, someone saw the piece at a festival. It was broadcast in France and Germany. The voice-over had to be translated, and they ended up having to use an actor. Channel Four, I feel, took a complete nose-dive in relation to the work. They showed Obsessive Becoming at 12:40 in the morning. This is a work that I labored over for five years, a work that has a tremendous impact on audiences, with a relevancy to many people's lives. This has been an amazing

experience for me. I'm not saying it's the best thing since sliced bread, but it was worth doing, and it gets to places that lots of things don't. So they put it on at 12:40 am, which is like throwing it away- really.

C.M-A: And they broadcast it just the once?

D.R: Just once.

C.M-A: That's extraordinary because usually there are a couple of screenings of this kind of work.

D.R: Yeah. Just the once and at a dreadful time. Yet the response within the film tours of colleges and universities and in all sorts of festivals has always been tremendous. People come up to me afterwards with a great deal of passion. It's a bit too much at times. The piece seems to break open something that some people have been stuck on for their whole life. I've sometimes been standing there with people weeping in my arms. You need some open and generous place to be in, other than just "Hi, I'm the film -maker" in order to be completely present with people in that condition.

C.M-A: I think because of the intimacy of the piece, they (the audience) feel they know you. Through the experience of watching it there's the sense of forming a kind of bond. People are presented with quite a lot of information about how you think, and how you feel.

D.R: And, more often then not, they are people who have some deep brokenness or pain that they haven't been able to talk about. They may have never been able to talk about it. But there is a kind of danger, there's this kind of "iky-sticky, feel-good" kind of thing that happens with all of this saccharine and repulsive infotainment where people are encouraged to reveal all the details of their lives for the "enjoyment of dying men" as Federico Garcia Lorca would have it. There's' a huge cringe factor inherent in the revelatory as it is expressed in our time. I went into my personal story so deeply because I didn't really have a choice. It’s very similar when I look back at Smothering Dreams. The two works are almost a matched set - dealing with those imponderables - things that you can hardly move on or deal with. I would make Smothering Dreams completely differently now, because my feelings about it have thoroughly changed.

Let me get back to the broadcast aspect. I made One With Everything and C4 put some money into that. It is a very broadcast worthy work. Its actually quite funny - its just not as funny as it could be, I don't think, and you really do need to come to it with some notion of a Zen tradition of iconoclastic humor. They didn't choose to broadcast it. David Curtis at the Arts Council said that it was probably to my benefit, because it means that I have the right to do so after a year. But look at what they do air day after day! Channel 4 came to me in Toronto in 1982 when Smothering Dreams was enjoying some of its first big public screenings. C4 was new then. Within 6 weeks we'd negotiated a deal. It seemed to me like a lot of money at the time. ($7-$8,000) which gave them the option to broadcast it twice. It wasn't until 1986, with the Falklands conflict intervening, that they eventually aired it. I was by then living in Scotland, so I had the pleasure of being here when it was broadcast. Other things have been made subsequently with contributions from C4, through John Wyver, "Ghosts in the Machine", and whatever schemes they had for ghettoising this kind of work.

When I set out to make a work I try, as much as possible, to divorce myself from the notion of an audience - that is a specific audience with certain needs. That is not to say that I cannot conceive of flipping the equation, and I do. It's just the way you make a painting. You have to stand in front of the work, or stand in some relationship to the work, and feel how it begins to accumulate, and how the meaning comes together. I work on a very intuitive level, and so I think I have, in the more successful works achieved my goal, although there is always the awkward

period, so it might be the less resolved segments of a work that haven't reached the kind of level I want them to. I often feel its in some way like a Guatemalan blanket with its perfect and symmetrical rows of red and blue ducks broken in one corner by the odd yellow duck. I have been told by the Ixil Mayans up in the altiplano of Guatemala that they purposely weave in a section that’s an imperfect match because they hold that no one can make anything perfect except for God.

Its an easy escape route if you are careless, but when you look at a finished work you will discover there are things that you haven't achieved. But if I had been burdened by broadcast pressures I would have found it completely obstructive and crippling. I don't think the work would have gone anywhere if I'd have thought that segments would have had to be made "simpler" or clearer, or somehow brought into a different focus because of the audience. For example someone said to me whilst I was making Obsessive Becoming that a lot of people would not understand the references to Rilke and Whitman. I always happily and forcibly resist that common reductionist tendency.

C.M-A: The reason I was thinking about the issue of the broadcast context in relation to Obsessive Becoming in particular, was this idea of something extremely intimate. When broadcast television comes into your personal space and you are sitting with the partner, or on your own. That's the power of

television, to come into your private and personal space...

D.R: If you have a context for it. What I find is a lot of people carry on a whole other life while television is on. I think that it is the rare person who will only turn on the television if they have a motive, or an aim. You could even walk into a room and just turn it on, that doesn't happen very often to me, but it might occasionally, and then something comes on that you are caught by or fascinated by that is worthwhile. But I think the problem with Obsessive Becoming, and this is why I shy away sometimes from showing it in a gathering or a dinner party, it just doesn't work because there is all sorts of other things going on and the work requires attention. You create conditions in order to offer an entry way for the person viewing it to merge with the work if they are willing to. There's the notion of the suspension of disbelief, that is one thing, but there's also the notion of dropping the armor a bit and suspending emotive blocks and the eternal tendency for the mind to agree or disagree. In this way you might allow something to penetrate a bit deeper into your consciousness. That is a bit difficult. So much of what comes off the television is all about trying to get you to buy something. It has been that way for years, but its getting worse as each year passes.

I would love to see Obsessive Becoming broadcast in Canada and the United States. It wouldn't have to be translated, and it has an American aura to it. I know that if it went out at 9:30 or 10 o'clock on PBS, it would have a tremendous impact. If there were a panel discussion afterwards or some sort of follow up, which I think would be very helpful, I wouldn't even have to be involved with that, you know there are other people, much more astute and knowledgeable about these things than myself, who could comment about the issues that are brought up. That would be gratifying to know that, not just in terms of my ego but that the work got out there and reached more people. This is the most powerful and vital aspect of broadcasting.

C.M-A: Shall we continue to discuss Obsessive Becoming, as that's the piece that I'm writing about.

D.R: It is definitely a process of amassing a huge palette of imagery and sound, a process of accumulation, and then there's an ongoing process of becoming familiar with the material that you've created or discovered, or transformed, or both. When I think of the various elements in Obsessive Becoming, the point where it all came together for me, was about two thirds of the way through making the program. I was getting up quite early in the morning to write. I went to Japan on a six month fellowship and that’s when I really started Obsessive Becoming. I began to write a kind of essay-narrative about my up-bringing, how strange it was, and what the costs were. There was continuing research into music and sound effects, there was a parallel effort going into dozens of hours of reel-to-reel audio tape that my parents had made.

When you listen to the boy's voices in Obsessive Becoming you're hearing my brother and myself in 1952 and '53, 54 & 55. The tape would never have been made the way it was without that fortuitous life material. I suppose that contributes to the level of intimacy that you spoke about. The other most consuming and exhausting and frustrating strand of that laboratory experience was finding a way, having worked with DVE, and ADO and Quantel digital optical devices since 1979-1980, to go beyond that at a fraction of the cost, because I was only able to work with those kinds of tools in laboratory situations where you would go into WNET as part of the television Lab and work with one of the editors there from say 7 o'clock in the evening to perhaps 5 or 6 o'clock in the morning. I lived in the outer Hebrides for three years, so I would fly to New York to work in a studio there, and would arrive with all my materials 90% produced. Then go through this wild transformative ride, not just responding to all the "bells and whistles" but to see how these things could apply directly to what you were making.

But in this instance I drew the line, and felt, as I had with all the films in one way or another, that it had to be born within the studio. If it was capped off or finally assembled in another studio, well that’s fine because then you have a pristine quality, if that’s what you want. You have work that you never have to go back and say "I wish the quality of the master was better than what it is.". There's a kind of technical virtuosity built into that. The effort with Obsessive Becoming began in about 1985 and all through the 5 years left in the 80's going from one Amiga to another. Why Amiga? I don't know. Because Amiga was ahead of everybody else in terms of image manipulation for still and moving imagery. Its amazing how its changed. 15 years on its like looking back to the stone age. I had everything that was available. I can't even remember some of the devices that I stuck onto the side of the Amiga. For example I had something called "Live", which was made in San Francisco for about a year and a half. You could scan in a really low-grade NTSC image and transform it. Then I had a "Video Toaster". All these things, but none of them were what I wanted.

I would do exhaustive tests and sketches. I wasn't satisfied with some low resolution cartoonish "video art" feel. I needed a level of image resolution that reflected the intensity of the material and that didn't diminish the emotional energy of the scenes. This allegiance to "quality" will get intentionally subverted at times so that if you are running a series of experiments and if you're applying an "Photoshop" filter to B&W or color footage that allows the edges to become vaporized and spread out in mysterious ways or turn to a kind of vapor that’s acceptable - at least you know that you're starting from some point of higher resolution.

What happened was that the learning curve of the software - the morphing programs, the compositing programs was very steep. I would pour through magazines to see month by month what was happening. So it was very much like an experimental scientific laboratory. I didn't necessarily build machines from scratch, but I sure as hell modified them. So I had lots of Amigas- 2000, 3000's and 4000's, in tower formations. It was a fairly complex unit, running throughout two floors of the house. I had to train two people, who worked full-time to actually do the things that I would learn. The "grounding' for all of this computer experimentation was - a 3 machine PAL Beta SP edit suite with an analogue video mixer.

C.M-A: So Obsessive Becoming was built over a long period time, working with a combination of domestic and professional equipment. The Amiga phase wasn't like a kind of sketch book, and after discovering the kinds of imagery you wanted you went to a facilities house with a kind of 'score' and recreated it at

a broadcast level.

D.R: No. It is mainly because I can not, and will not work that way. Maybe its just cannot, and therefore will not, but I take voluminous notes and I study the material to the point where the material becomes second nature to me. All I need help at that point is to find it and to access it with relative ease. When you are generating the fiftieth take of a certain kind of transition involving, say, this black and white silhouetted morph moving into another shape, then you need to know where it is. There's an intense process of cataloging and creating little pictures or thumbnails that were not generated automatically at that point to provide accessibility. You need to know what you have and where things are. I was backing everything up on DAT by the final two years The system, if I can describe it briefly, ended up being seven different computers at least three of which were emulating Macintosh operating systems. The break came when a company in Canada called DPS I believe, marketed something known as the "Personal Animation Recorder". They cost about $2000. each at that time. Along with the computer work stations there were many hard drives which could work at the speeds necessary to feed the material in and then retrieve it. Using the Macintosh emulators I was able to use Photoshop filters through the Amiga using live video and then render it frame by frame. So I would set up a sequence that might take all weekend to render, then I would make a judgment about those results, and perhaps go back and correct, constantly backing up with DAT. In retrospect I can not remember going back to the DAT, but at least we knew if we needed it we had it. There were drawers full of DAT tapes.

But it was a wonderful feeling. I can only imagine that it must be like this for a scientist, or the sadhu finally able to separate milk from water, or whatever! Finally there was this...I think it was the footage of the little boys with the hoop in the street - I had been able to strip out most of the detail and leave the figures of the boys and let everything else wash out to white. So as opposed to the black that I started out with in Thousands Watch, suddenly there as this white matrix that's used from the beginning to the end. That's a visual theme in Obsessive Becoming.

Through all the systems there's a term that I thought of as "techno-cumbersome"- that’s what they are. I would get a shipment of an Amiga 3000 tower from New York for example. Upon arrival it wouldn't work - a board had been jostled, chips loosened, cables undone. What I ended up training myself to do was to completely take the machines apart and put them back together again. I guess that appealed to some 'boy' nature in me too...

CM-A: I'm just wondering if that experience changed the way that you thought about the medium. We were talking earlier about taking the frame apart. Here you are getting into the guts of the technology at the detail level. It must have affected the way you saw the image.

D.R: I think so. You begin to understand how the fields and the frames and the pixels relate to each other. At some point you want to make the poetic leap beyond mere technology and you do, you must. The leap of poetry that Robert Bly alludes to in his work, where even though you know all that, you jump beyond it. Somehow the image just stands above itself.

C.M-A: Its another kind of knowledge isn't it. Because its like knowledge through the body. You are becoming a kind of sculptor because you're working with the material which constitutes the image in a physical and tactile way your understanding is increasingly from the "inside". It seems to me that the material of video is not just this texture on the screen, or this "mosaic" as McLuhan called it. You end up with an intimate understanding of what the image is, how its configured, how its produced. You know it physically.

D.R: And yet its also quite illusory. There's this mass of jumbled information that can somehow be reconfigured if you chose to. Yet it is there silently persisting in the background. There's some part of me that’s empowered and informed by a more eclectic Renaissance methodology - a way of working that allows me to make a work like Obsessive Becoming. There has to be some element of the work that is absolutely imperative for your survival - that the work must get made. There's a great deal that doesn't come out in Obsessive Becoming. There are a number of things that are deliberately

left ambivalent, enigmatic - not necessarily ambiguous but open to many interpretations. But for that work to occur, I was considering massive amounts of history, and other writing and essays which inform the work.

For example, and this will curve back into the technical aspects as well, but its all part and parcel of it. There's a book by the poet Susan Griffin, that fortunately I didn't find until four months before the final edit. Her book is called A Chorus of Stones: The Private Life of War. I can't think of a single document that exists which is as much like Obsessive Becoming as her book is. She traces a very dark history of someone in her family being abused by a parent, and the mystery of their disappearance from the family. She weaves, in this marvelous tapestry - the life of the molecule, the life of Enrico Fermi, the boyhood of Himmler, the story of women working at the Oakridge nuclear facility in Tennessee-, the accidental death of her father - all of these 20th century historical figures and these precious personal histories are embedded, layered and woven through each other in a gentle but completely tour de force way. The impact is tremendous. It really shaped my thinking concerning the relationship of personal narrative and the historical dimension.

There is a credit at the end of Obsessive Becoming for various people, some of them are spiritual teachers, others are essayists and poets, all of that beautiful power flows into the work. It was a demanding process. I'm not a scientist, and the technical aspects of keeping that together were very demanding, making sure that people knew what they were doing from day to day. The fact that there was very little money was always a problem. It's sometimes a miracle that the thing doesn't collapse inwardly.

I haven't thought about this question you are asking about the signal, but clearly I do feel as if I was sculpting the material in some way. The only way that I can work at these things, and it may be a flaw at times, and also the cause for those aspects I find deficient in the structure, is that I always produce tremendous amounts of material and then begin to make experimental relationships with that work over and over. I do not have an a priori grand design in terms of structure in the same way that I have oftenhad with the installation work. So as I go along there are poems that are being written- prose poems, and then I look at the relationships that are formed between these and the ever expanding basket of imagery, sound and text.

My daughter Adele was born a third of the way through the production- I was 45 at the time she was born. Both of my parents died whilst I was making it. There was a very active emotional foment in my life that I think is evident in the work. I can remember that I was in America, after my step-father died and finally I had a non obstructed relationship with my mother, or a potential one, that wasn't encumbered by his presence. And lo and behold within two weeks, my mother was diagnosed with incurable cancer. So I spent 8 months over there with her. When she was finally slipping in to a coma, I had this epic battle with the nurse because she thought it was a horrible thing that I should want to video tape my mother as she was dying. And yet for me it was essentially reverential - acute attention to her passing - it was impossible not to do it. I didn't have those conflicts, the nurse projected those conflicts on to me. The home help nurse was just disgusted that I would videotape my mother's death. And yet, its a singularly moving piece of imagery that recurs several times and its not used gratuitously or it is not used in a way that demonstrates anything short of complete respect for her struggle with life and death. Its amazing to see how her face begins to look the way she did when she was a child. There's the image of Linda, my wife at the time, who was a tremendous help, giving my mother water through a syringe.

Some people become frustrated with Obsessive Becoming because there's no map - nothing is totally spelled out. The relationships are somewhat unclear - who is who to who. To present the undefined has always been a working method of mine because I sense that it allows people - I'm almost positive that it allows people to enter into the work more fully. It has been said by those much wiser than I that there never is any fixed resolution - there never is any ultimate unchanging quality I believe, in anything. So likewise there is no definitive clarity, there's no end product, there's no result, its like the words that are embedded in the early passages of the film- "no place to go, nothing to do, nothing to be".

I remember coming back home to Scotland with the tapes of my mothers death, and it was a year before I could even think about looking at it. There was all this unresolved business, which we always have with our parents. I remember sitting down in the studio, surrounded by these banks of equipment and putting this tape in and seeing my dear mother in her last hours. And its all that you can do, just to sit there and have the release of being able to weep for her, and for yourself. I was in this condition of deep vulnerability. I think this kind of intimacy in the work was very, very important. I don't know that I even voiced it internally. But I knew that the work had to possess a resonance of sincerity and authenticity - as if you were talking to your beloved in the way that is only possible if you allow yourself the space of intimacy that is beyond self consciousness and artifice. To allow yourself to be quiet enough to hear the truth, or whatever that ineffable bubbling up is, to finally come through. That resounds in the work, and that's a quality that can be found in a masterful painting. How to put it into a film or a video is a curious proposition.

When I went to record my voice over, I bought the best microphone that I could possibly afford. I bought a Neueman microphone - A wonderful instrument- the Stradivarius of microphones! Then I built a little booth in the corner of the room and I bought the best recorder that I could afford. I used a little

bit of whisky to keep my voice soft and my head together. The poem that I wrote for the ending in many ways had been a gift. it was the product of months and months of getting up at four in the morning and working to write I'd worked with a book called Writing for Your Life: Exploring the Inner Worlds, a brilliant treatise on writing by Deena Metzger published by Harper and Collins. I had known Deena some years before, she'd been a mentor in a veteran's retreat in 1989 when the Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh gave the first retreat for Viet Nam combat veterans in Santa Barbara. The prose poem at the end of Obsessive Becoming came unexpectedly. Suddenly one morning I got up and all this was there, it took forty minutes to sketch out, it was edited a few times and it forms the trajectory of the end of the film. And if people are open to it and have issues that they are trying to work with, that's where it begins to come together. Clearly for me, when I was recording the voice, it was important to have the emotion present, not to create or to synthesize sentiment, but to be in the emotional timbre and register that was appropriate to that passage.

Some critics disagree with that, they think there's a seduction going on, but its not meant in that way. Some people feel the music is a seduction. Everybody has a different response to these problems, some chose to ignore them, or employ different methods of either approaching them or avoiding them. These were the working tools that I came up with. I might never

use them again in that way.

Someone said to me- actually it was Patty Zimmermann, whose insight into the work is as sharp as any. She said: "But your body never appears in this work." Its not completely true, because there's a dreadfully embarrassing scene where, the day after I buried my mother, the same afternoon actually, I disposed of my stepfathers handgun. For 50 years my parents had been living with this fucking pistol. Milton, my stepfather, was a gangster. Milton was a person who would use a pistol, and keep it on his person all the time and sleep with it right next to his head in the bed board. He had at one point walked my brother up the long drive at our home with the pistol pointed at his back. I'd seen him shoot at people. I know that in his early life he'd witnessed murders, possibly been involved with them - I don't know.

But I do know that my mother adopted the pistol after my father died and continued to sleep with the pistol, and continued to spin out the fantasies and the neurosis and paranoia of "you gotta have a pistol or you're not a safe person". I couldn't wait to get rid of the pistol. The only way for me to get rid of it - a huge 38 snub-nose revolver with police special bullets in it, was to literally do it 'on camera', and put it in a place that I thought it would be safe - that's with the snapping turtles and Water Moccasins, in the mud. So there was this six acre lake, which goes back to the blowing up of the dam in 1963 , it just occurs to me now. There's an amazing circularity to things, which you don't become aware of until years later. I was severely strung out. I'm really rough and looking awful, which is great, because if you can see yourself and witness all the self-consciousness and vanity you might just get a teaching. You have a puffy face, don't know what you're doing with the gun and you're tempted to fire it, but know you don't want to fire a weapon, you've had enough experience firing weapons, so you just sort of invent a performance - throw in the bullets and then toss the pistol far out into the lake. Someone who is untrained is holding the camera and captures it on the fly - still its a moment....So Patty says my body isn't in it, and it isn't, in the sense she was talking about. I don't know, maybe I get people to stand in for my own body more often than not.

C.M-A: I just think that there's this kind of physical/emotional relationship to the medium that goes all the way through the work. You've described the complex layers of working; building the machines, getting into the guts, breaking the frame to compose images. If that isn't an activity of the body, I don't know what is. An image of the body is one thing, but the embodiment of the person is there at a very deep level.

D.R: Well, Patty correctly touched on something. I hate mirrors. I don't mind shaving in a mirror because of the utilitarian function of the reflection, but I can't tolerate sitting at a table in a restaurant where there's a mirror and I can see myself. So there's a certain neurosis that you just live with and laugh about.

C.M-A: But the whole tape is at one level about you and your experiences, and so to have you in it physically would be almost too much to bear.

D.R: I think it would be indulgent and that weakens a lot of work these days. People can't wait to throw themselves in front of the camera. Some people can do it with great acuity and skill, and they work with their bodies in a wonderful way. I have some friends: Helen Bendon and Jo Lansley, they're doing some great things with the body. There is a scene in Smothering Dreams which comes up near the beginning. The boy, who is clearly myself, sees himself in a mirror and he picks up a stone and shatters the mirror.

C.M-A: There's a tie in here about your own spiritual/ philosophical outlook and the capability of that to the medium of video. I wanted to layer into that the issue of video and narcissism. Early Artist's video in the late 1960's- the sort of work that began as documentation of performance work - the use of video as a kind of 'electronic mirror'; a method of using video to look at themselves and their interactions .

D.R: Are you talking about Vito Acconci?

C.M-A: Yes, Acconci, and others.. There were other performance artists, a lot of women artists used themselves and their bodies, and made tapes about femininity and feminine experience. There is clearly a strong influence of feminist work in Obsessive Becoming .You have mentioned a number of literary influences, but there is this larger issue of the "personal as political". The relationship between the intimate- the individual person and some larger manifestation - the social sphere.

D.R: My entry into a metaphysical dialogue starts with the end of my time at war. When you start talking about spiritual practice, its potentially such a lame and unconvincing exercise.

Yet we need words to talk about those things. The problem is that spiritual practice can also mean spiritual materialism and spiritual bypass. When I look at my own history I see it as something that you learn by doing. You succumb to it and you work your way out of it. The vogue for Buddhist practice sometimes is very chic and hip, or has been. But if you don't enter it in that accessorize way that favors style over substance you may find whatever understanding you need. Whether its Christian mysticism or Sufi practice or some other vital indigenous practice, or gardening practice, or whatever it is that allows you to see your connection to other people and other things, it can be extraordinarily valuable and rewarding.

Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese Zen teacher who I have studied with since 1988, has often referred in his talks and writings to the notion of the "historical dimension" and the "ultimate dimension". The ultimate dimension could perhaps be seen as the long view, the over view. For instance if you are in an immense argument with your spouse or your partner about something that is born of great discord, there is some quality in you that will allow you to stop and say "wait a minute, what will our faces be like in 300 years?" You can ask yourself how important is my winning of this, or my ability to state my case? Where is the lack of understanding that is on display here that’s not allowing us to see ourselves in this other dimension?" It's what you some folks refer to as 'heaven" except its right here and now. It's the dimension where you can experience your mother in the palm of your own hand, even if she's dead- particularly if she's dead. The historical dimension is the everyday world of measurable name and form.

So when I think about the war, I see myself extracted from that ambush almost miraculously and going on in life while so many around me ceased to be, at least in the historical dimension. There's a shamanistic feel to it. What is the wounding that's happening here (and I can only see that from this great distance) why am I being able to survive this madness when I'm linked at the navel with my lieutenant who is destroyed in a matter of seconds with a deluge of machine gun fire? Everybody around me is dying and I'm there for four or five hours with a constant and anguished reiteration of death. I get into a helicopter and the helicopter is shot through and through with small arms fire and then I get to the field hospital and the hospital is shelled. So you find yourself floating above a bed a few steps from what you thought was your body...

My spiritual life obviously began along time before that, but that's where I was broken open - deeply enough- traumatically enough, suddenly to be aware of something else that I had missed all along. The historical dimension is being in the midst of this unfolding tragedy.

It's curious that I stood in -22 degree F. weather, very frigid conditions, on Jan 20th, 1961, for Kennedy's inauguration. I was born and raised in Washington DC, and it was a magical time. I was there with my older brother Tom to witness this great historic procession, and then seven years later, exactly to the day, I'm lost in this hell hole, and then somehow I'm extracted from this tormented realm and then I spend the next ten years- more, trying to make some sense of it. What came up immediately and matured within a couple of years was that I began to track down the mystery that I had noticed on that dreadful day along the DMZ. Then of course, like a lot of people in those times, I experimented deeply with mind expanding substances. I traveled to Central America and consumed mushrooms, peyote, mescaline. Normal reality began to unfold along different paths, sometimes in weird and wonderful and dangerous ways. It wasn't until after trying for almost ten years to learn to meditate that I was given - offered meditation by a tantric master, and I pursued that with a great passion. But until I began to witness my own self as one who was worthy of love and started to explore much deeper into all these mysteries that I was actually able to enter into work that was clear. That was the most immediate gift of that process of centering.

Its about slowing down, its about taking notice, paying attention and seeing things that you might intuit, but not completely know as gifts of insight. That kind of gift - call it faith if you like, or the perception that there exists in this world an extraordinarily deep connection between everything that exists. There's this tremendous yet ineffable otherness that you can avoid forever by being very busy or being lost in an identity, like "I'm the artist and I'm making this much money, or not making this much money".

To speak very succinctly about this interrelationship with the work, while I was working on Obsessive Becoming in particular, the challenges were often so great that at times I would completely remove myself from the work. For example going on a silent retreat for a month, where you're not speaking to any one about anything at all except perhaps a teacher once a week to have a brief interview. Doing hours and hours of formal sitting meditation when your world becomes reduced to dealing with your store of grief. During that period, which was about halfway through the work, right before my daughter Adele was born I went to Gaia House, the insight meditation center in Devon, for a month of silent retreat. The first week was spent pondering the war, all of that sad time just coming up in a rush. It happened to be Guy Fawkes week, and the retreat was near a rifle range. It was extraordinary, I would sit there in the meditation hall and hear the weapons and the exploding fireworks and occasionally there would be a helicopter going over, and it was all served up yet again. After I got through dealing with that, the family issues came up and all the torment and torture and loss and the horror and grief. Its was like - for the tape to be made - that turning toward and into the grief had to work or there would be nothing to say.

A couple of years ago, and this voice is embedded in the tape, Thich Nhat Hanh began to talk about his mother during a retreat I attended in France. He is such a poet and a completely

humble and authentic human being that his words have this incredible reserve of power and meaning - there's no artifice. He suggests to us that if you can visualize your parents as children and see what formed them as children, you might open a gateway to compassionate understanding. He's asking us to consider these things from a much deeper perspective than some erudite psychological view. He's saying that it’s possible to have the inner vision to see your parents in this way. That was a process that really began to open things up for me, because I had a lot of grievances against my parents.

I went back to interview the two remaining siblings after my parents had died - my stepfather's only surviving sister and my mother's only surviving sister. Neither of them are deep philosophical thinkers, but they are very alive, with all their wits

about them and they can remember childhood together with Milton and Sue. Looking at the images of them and hearing their stories as children, going through these hours of material - I interviewed both of those people for ten or twelve hours each. It's all kind of an unrehearsed chorus of these fragments of memory streaming along. You reach epiphanies, and you reach certain understandings, denouements, and breakthroughs.

I suppose if I have my reservations about the work it's that structurally it isn't as perfect as I would like it to be. That's OK, I can live with it. I would never go back and change it. But I think all of those searches paid off. What's interesting about 'video', whatever that is, is that it does create the possibility of this grand fusion of materials. I always have at some stage what I call a marriage edit, a final edit where all the reels are brought together and all the segments are embedded in the finest- wine- the best tape format that you can afford.

C.M-A: How and when did you initially begin to work with video?

D.R: I went back to college under a veteran's rehabilitation program. I had been medivaced from the battle field, as it were, in January of 1968, and then had spent seven months in a military hospital and afterwards had about another year and a half to serve. During the last 6 months of my 4 year enlistment there was something called "project transition "which was notionally an effort to give combat veterans some other job skill, besides operating an M60 machine gun. In my case I was a field radio operator with a grunt platoon so it wasn't too far-fetched that I might study broadcasting. I was station at Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia and I opted to study at the National Academy of Broadcasting in my hometown, Washington D.C. not so far away. So I enrolled in the Academy studied radio and television there 40 hours a week during my last 6 months of my four year enlistment. This was my first contact with the Sony video portapak during the summer of 1969. The curriculum was designed to get you behind the desk as a radio announcer or TV personality, and that of course meant wearing a suit and being a slave to a schedule having just spent four years wearing a variety of suits that Thoreau would have mocked with gusto of one kind or another and trussed up in duty I got cold feet of the highest order, so I took my diploma and all those assertive and persuasive mouth skills that I had learned and just vanished into the countryside.

I lived in the woods in Maine in small cabin for about 3 years completely off the grid until I began to get restless. Then in 1973, I went to college under a disabled veterans rehabilitation program. This got me out of my "wounded retreat" brought on by shock of the combat, which was deeply traumatic, but my sense of betrayal had also forced a rupture with society that had undermined the foundations of my own metaphysical being. Somehow it was easy for me to link what was happening in the war to what was happening on the home front, or anywhere in the Western world in 1968 for that matter. What I perceived was that the war was about money and greed, xenophobia, racism all those things that were such deep and abiding flaws in our society. I felt poisoned by it all. So when I decided to re-emerge, I went to study journalism and early in my studies the great photographer & documentary film maker Willard Van Dyke showed up to run an intensive 3 month film workshop, which I attended with great enthusiasm. That summer was really a rebirth in so many ways as it became clear to me that working with a motion picture camera was somehow second nature to me. I had some previous experience - years before my stepfather had a 16 mm camera that was religiously hauled out for family rituals and events. The first film footage I recorded in my life, when I was 14 years old, was of a dam explosion, which seems kind of ironic looking back. My stepfather had contracted to build a six acre lake and the contractor and I spent days packing the dam core with dynamite resulting in a spectacular explosion which I filmed. So I began to study film, and my second contact with video was as a cinematography major. As part of the course you had to do one project in the TV studio. The problem was that it was very broadcast oriented, once again. So I did a short assignment- a camera podium piece where I worked with images from Northern Ireland- it was something that deeply interested me- I could never work on anything that I didn't interest me, even if it was an assignment. But because of the studio orientation and all the suits and clap-trap, I was still much more interested in film and still cameras than any work in what I might do in a neurotic and glamour addicted broadcast industry. After graduation I went away for 6 months to India, which was a very transformative experience on every level.

After returning, from India in January 1979, I got a position at Cornell University in the educational television department. I began to work with some film material which I had intended to use to make a reply to a film by Robert

Gardener entitled Dead Birds that he had made after taking part in an anthropological expedition in New Guinea. It was a project begun before I went to India, but that I had previously been unable to complete, as I simply could not resolve the structure and the ending. At Cornell ETV I had a kind of "Eureka" moment when I was able to sit down at the U-matic video editing system and learn the technical skills from my good friend and colleague Jon Hilton. I transferred all the film footage to video and it was precisely the plasticity, the spontaneity and the very smallish gap between inspiration and execution that was very engaging for me. I then transferred all of this imagery, 3 or 4 hours of film material that I had researched and selected from the National Archives in Washington.

That process of going back and digging deeply into archival footage wasn't a common practice at that point. I had never been able to make sense of this material even though it was what I had chosen myself. But when I transferred this material to Quad (2 inch video) I was able to modify the footage, change the contrast, add color, solarize and process shots in a completely new way for me. I created quite a few effects reels from the footage as well as the straight transfers. Jon and I made a decision to leave the sound out completely until the piece was edited. I could see and felt very strongly that the work that I wanted to make was about the sense of how the West particularly America, was always constantly balanced on the edge of nuclear suicide. As a society we didn't talk about it very much and rarely acknowledged it publicly except for certain notions about fall-out shelters and civil defense, and all the bizarre drills and schemes that came out later in wonderful pieces like Atomic Cafe.

So I ended up making a video work called Thousands Watch (1979). Its only 7 minutes long and effectively merges this footage from the 1957 Brussels World's Fair, film footage from Las Vegas and New York, archival war footage, and most importantly, black and white and color footage from Japanese film units at Hiroshima that had been confiscated and had only been released in 1975. These stunning film reels had sat locked away in a vault at the Army Film Archives for 30 years. The graphic horror of the event was very much a closely guarded state secret. So by transferring this material to video I was able to explore a new approach. Footage could be modified in real time and merged - at that time I wanted nothing to do with cuts. Cuts have rarely occurred in my work since then. I have, I suppose, an eternal notion of the fluidity that pervades the fabric of this world. But in the case of this piece, since it was only a 2 machine suite, and there was no time-base corrector or anything like that, the way I achieved the fluidity was by the simple creation of a black matrix which everything arose from, sustained, and subsided back into.

Thousands Watch piece was very successful, and was included in many festivals, which resulted in my being awarded my first NEA fellowship. After that I then went on to make Smothering Dreams. (1981). This was a real turning point because no one had made that kind of work dealing with that nuclear issues before. For me at that point, it became clear that the medium was going to allow me to make the work that I wanted to make. I think that within a month or two of making Thousands Watch I made a list of the works that I wanted to make, and all of them have been made. Obsessive Becoming (1995) is one of the last on that list, I think I then called it Seeds of Destruction.

C.M-A: Which aspects of the video medium do you consider to be the most important?

D.R: I became really enamored with and encouraged by the feeling that the video camera could be employed directly as a tool (within certain restrictions) in the same manner that a pen, or a brush or a carving tool is used. I had learned traditional art processes as well by this stage. Carving wood, and painting all of the doors and windows of my room, making sculptures with toy soldiers were early forays into art and some way of reaching for a catharsis, some means of being able to digest these violent experiences, or even being able to simply hold them in a real way. Discovering that I could now go out into the world with the camera, although it was still a relatively clumsy 3/4 inch U-matic recording deck. But clumsy or not, it went on a back-pack, and with the camera you could just capture things right there, and look at them instantly if you chose to. That relationship has now gone on for years, but to chart the changes over the years since then, I would look at the camera system first.

I had access to one inch in the field within a year or so, when Cornell got their first one inch type 'C ' machine. They were very generous when I was working on Smothering Dreams. I could rent a $48,000 'State of the Art' RCA 3 tube camera, with a Sony 'Type C' one inch portable recorder. So I had access to over $100,000 worth of equipment, renting for usually about $100 per day. I could take it home for the weekend, and work with the young actor who was in Smothering Dreams - just the two of us. The intimacy level is expansive, its very present. Setting up these shots with toy soldiers with 'Cherry Bombs' buried underneath them; I was trying to create a different landscape of the imagination - a dream world with the child looking at the soldier, and the soldier looking at the child.

So through the years, I would take notice every time there was a new technical development in field recording. For me this was not so much an issue of technical quality (although that interested me) but it was more that the camera became more and more of an extension of my own body. So whenever anything truly innovative came out in the marketplace, I would often be among the first to use these new systems. I had the first consumer level camcorder. It was a new format, brought out by JVC as VHS C. In the early 80's as soon as it was available, I went to "47th St. Photo" and bought the deck, the camera and this "marriage" device, which I used. I would wander for hours making what I called "ribbons"- I would move the camera, following for example, a battered tin pot (in a scene which shows up in Ganapati: Spirit in the Bush (1986) floating down the stream. Following the edges of tree forms, etc. You know- like having another eye in which you could pick up anything and everything.

From there it went to Video 8, High 8, SVHS. Every year or so changing my camera system. Now you can go out and buy a decent 3 chip digital camera for $1500. I went to India on a Guggenheim fellowship and I managed to convince Sony to sell me a BVP 110 and a BVP 50 at dealer cost, so I spent about $12,000 and I had a single tube broadcast quality set up to travel with. The whole configuration of camera and deck was designed for journalism and combat footage. I had never seen a camera that was so ergonomically designed (of course it’s a dinosaur now) It had a handle built into the top, an incredibly low profile, with a wonderful Fujinon zoom lens. The BVU 50, weighed about 15 pounds, it was 'record only'- you couldn't play back in the field, but by that time I was so conversant and familiar with the equipment and so confident that the footage would be there. I spent a whole lot of time traveling through France, Wales, Spain, and a few months in India before I saw a single frame of the footage. Much of the material from India was used in Sabda (1984).

So the technology has changed considerably. Right now I'm in a fallow period where I've made Obsessive Becoming which took 5 years to complete - the whole strange, alchemical process of putting that piece together. Since then I've made this piece called One With Everything (2000) which has practically been my undoing. I can understand why Woody Vasulka would say "I'm not sure that I believe in this single screen durational approach to working." I can't say that I've gone off it completely, but I came out of Obsessive Becoming with some sense of gratification. When I began to work on One With Everything, I decided to change my working method after being asked to deliver a finished work before a year was out. So I got 15 or 16 people together- the production values are very high. It was a disaster. Its been in lots of festivals, but I'm never happy with it. Like Woody I can look back and say "That doesn't work the way it should work".

Going back to what we were talking about...I'm at the point where I don't own a video camera. I've got enough distance from it now... You can travel around now with a shoe box containing all you need. You don't have to have that big suitcase full of equipment, but there's a trade off- because of the proliferation of digital effects, devices, potentials and possibilities within the camera and within the PC and Mac systems, etc., I would be completely bewildered if I was just starting out. It's as if you have to thread your way through this far too rich circus of delightful and complicated offerings just to begin the real work. I'm not saying this from a Luddite position, or that we should strip our cameras down and do pure black and white, but I sometimes go out and shoot something with Super 8 just because there's an aspect about it that is crude pristine and unpredictable.

C.M-A: Maybe its all got too controllable- too predictable.

D.R: To some extent. I'm a bit fed up with the learning curve. With Obsessive Becoming it wasn't five years in production - it was closer to ten years because I started in '85 with my first Amiga, and it wasn't till '93- almost '94 when I finally went "Aha!" This is the dream world that I wanted to get to. To be able to tear an image apart and re-form the image with complete freedom. Even though you are only working in two dimensions, its the apparent three dimensionality that matters.

C.M-A: Can you talk a little bit about your relationship to broadcast TV. What is the relationship between broadcast TV and your work?

D.R: I don't know whether I've come full circle or whether I've become completely jaded. Everything that I've ever made has ended up being broadcast in one form or another. Obsessive Becoming was picked up by "La Sept Arte". This was a tremendous boost in sales, someone saw the piece at a festival. It was broadcast in France and Germany. The voice-over had to be translated, and they ended up having to use an actor. Channel Four, I feel, took a complete nose-dive in relation to the work. They showed Obsessive Becoming at 12:40 in the morning. This is a work that I labored over for five years, a work that has a tremendous impact on audiences, with a relevancy to many people's lives. This has been an amazing

experience for me. I'm not saying it's the best thing since sliced bread, but it was worth doing, and it gets to places that lots of things don't. So they put it on at 12:40 am, which is like throwing it away- really.

C.M-A: And they broadcast it just the once?

D.R: Just once.

C.M-A: That's extraordinary because usually there are a couple of screenings of this kind of work.

D.R: Yeah. Just the once and at a dreadful time. Yet the response within the film tours of colleges and universities and in all sorts of festivals has always been tremendous. People come up to me afterwards with a great deal of passion. It's a bit too much at times. The piece seems to break open something that some people have been stuck on for their whole life. I've sometimes been standing there with people weeping in my arms. You need some open and generous place to be in, other than just "Hi, I'm the film -maker" in order to be completely present with people in that condition.

C.M-A: I think because of the intimacy of the piece, they (the audience) feel they know you. Through the experience of watching it there's the sense of forming a kind of bond. People are presented with quite a lot of information about how you think, and how you feel.

D.R: And, more often then not, they are people who have some deep brokenness or pain that they haven't been able to talk about. They may have never been able to talk about it. But there is a kind of danger, there's this kind of "iky-sticky, feel-good" kind of thing that happens with all of this saccharine and repulsive infotainment where people are encouraged to reveal all the details of their lives for the "enjoyment of dying men" as Federico Garcia Lorca would have it. There's' a huge cringe factor inherent in the revelatory as it is expressed in our time. I went into my personal story so deeply because I didn't really have a choice. It’s very similar when I look back at Smothering Dreams. The two works are almost a matched set - dealing with those imponderables - things that you can hardly move on or deal with. I would make Smothering Dreams completely differently now, because my feelings about it have thoroughly changed.

Let me get back to the broadcast aspect. I made One With Everything and C4 put some money into that. It is a very broadcast worthy work. Its actually quite funny - its just not as funny as it could be, I don't think, and you really do need to come to it with some notion of a Zen tradition of iconoclastic humor. They didn't choose to broadcast it. David Curtis at the Arts Council said that it was probably to my benefit, because it means that I have the right to do so after a year. But look at what they do air day after day! Channel 4 came to me in Toronto in 1982 when Smothering Dreams was enjoying some of its first big public screenings. C4 was new then. Within 6 weeks we'd negotiated a deal. It seemed to me like a lot of money at the time. ($7-$8,000) which gave them the option to broadcast it twice. It wasn't until 1986, with the Falklands conflict intervening, that they eventually aired it. I was by then living in Scotland, so I had the pleasure of being here when it was broadcast. Other things have been made subsequently with contributions from C4, through John Wyver, "Ghosts in the Machine", and whatever schemes they had for ghettoising this kind of work.

When I set out to make a work I try, as much as possible, to divorce myself from the notion of an audience - that is a specific audience with certain needs. That is not to say that I cannot conceive of flipping the equation, and I do. It's just the way you make a painting. You have to stand in front of the work, or stand in some relationship to the work, and feel how it begins to accumulate, and how the meaning comes together. I work on a very intuitive level, and so I think I have, in the more successful works achieved my goal, although there is always the awkward

period, so it might be the less resolved segments of a work that haven't reached the kind of level I want them to. I often feel its in some way like a Guatemalan blanket with its perfect and symmetrical rows of red and blue ducks broken in one corner by the odd yellow duck. I have been told by the Ixil Mayans up in the altiplano of Guatemala that they purposely weave in a section that’s an imperfect match because they hold that no one can make anything perfect except for God.

Its an easy escape route if you are careless, but when you look at a finished work you will discover there are things that you haven't achieved. But if I had been burdened by broadcast pressures I would have found it completely obstructive and crippling. I don't think the work would have gone anywhere if I'd have thought that segments would have had to be made "simpler" or clearer, or somehow brought into a different focus because of the audience. For example someone said to me whilst I was making Obsessive Becoming that a lot of people would not understand the references to Rilke and Whitman. I always happily and forcibly resist that common reductionist tendency.

C.M-A: The reason I was thinking about the issue of the broadcast context in relation to Obsessive Becoming in particular, was this idea of something extremely intimate. When broadcast television comes into your personal space and you are sitting with the partner, or on your own. That's the power of

television, to come into your private and personal space...

D.R: If you have a context for it. What I find is a lot of people carry on a whole other life while television is on. I think that it is the rare person who will only turn on the television if they have a motive, or an aim. You could even walk into a room and just turn it on, that doesn't happen very often to me, but it might occasionally, and then something comes on that you are caught by or fascinated by that is worthwhile. But I think the problem with Obsessive Becoming, and this is why I shy away sometimes from showing it in a gathering or a dinner party, it just doesn't work because there is all sorts of other things going on and the work requires attention. You create conditions in order to offer an entry way for the person viewing it to merge with the work if they are willing to. There's the notion of the suspension of disbelief, that is one thing, but there's also the notion of dropping the armor a bit and suspending emotive blocks and the eternal tendency for the mind to agree or disagree. In this way you might allow something to penetrate a bit deeper into your consciousness. That is a bit difficult. So much of what comes off the television is all about trying to get you to buy something. It has been that way for years, but its getting worse as each year passes.

I would love to see Obsessive Becoming broadcast in Canada and the United States. It wouldn't have to be translated, and it has an American aura to it. I know that if it went out at 9:30 or 10 o'clock on PBS, it would have a tremendous impact. If there were a panel discussion afterwards or some sort of follow up, which I think would be very helpful, I wouldn't even have to be involved with that, you know there are other people, much more astute and knowledgeable about these things than myself, who could comment about the issues that are brought up. That would be gratifying to know that, not just in terms of my ego but that the work got out there and reached more people. This is the most powerful and vital aspect of broadcasting.

C.M-A: Shall we continue to discuss Obsessive Becoming, as that's the piece that I'm writing about.

D.R: It is definitely a process of amassing a huge palette of imagery and sound, a process of accumulation, and then there's an ongoing process of becoming familiar with the material that you've created or discovered, or transformed, or both. When I think of the various elements in Obsessive Becoming, the point where it all came together for me, was about two thirds of the way through making the program. I was getting up quite early in the morning to write. I went to Japan on a six month fellowship and that’s when I really started Obsessive Becoming. I began to write a kind of essay-narrative about my up-bringing, how strange it was, and what the costs were. There was continuing research into music and sound effects, there was a parallel effort going into dozens of hours of reel-to-reel audio tape that my parents had made.

When you listen to the boy's voices in Obsessive Becoming you're hearing my brother and myself in 1952 and '53, 54 & 55. The tape would never have been made the way it was without that fortuitous life material. I suppose that contributes to the level of intimacy that you spoke about. The other most consuming and exhausting and frustrating strand of that laboratory experience was finding a way, having worked with DVE, and ADO and Quantel digital optical devices since 1979-1980, to go beyond that at a fraction of the cost, because I was only able to work with those kinds of tools in laboratory situations where you would go into WNET as part of the television Lab and work with one of the editors there from say 7 o'clock in the evening to perhaps 5 or 6 o'clock in the morning. I lived in the outer Hebrides for three years, so I would fly to New York to work in a studio there, and would arrive with all my materials 90% produced. Then go through this wild transformative ride, not just responding to all the "bells and whistles" but to see how these things could apply directly to what you were making.

But in this instance I drew the line, and felt, as I had with all the films in one way or another, that it had to be born within the studio. If it was capped off or finally assembled in another studio, well that’s fine because then you have a pristine quality, if that’s what you want. You have work that you never have to go back and say "I wish the quality of the master was better than what it is.". There's a kind of technical virtuosity built into that. The effort with Obsessive Becoming began in about 1985 and all through the 5 years left in the 80's going from one Amiga to another. Why Amiga? I don't know. Because Amiga was ahead of everybody else in terms of image manipulation for still and moving imagery. Its amazing how its changed. 15 years on its like looking back to the stone age. I had everything that was available. I can't even remember some of the devices that I stuck onto the side of the Amiga. For example I had something called "Live", which was made in San Francisco for about a year and a half. You could scan in a really low-grade NTSC image and transform it. Then I had a "Video Toaster". All these things, but none of them were what I wanted.

I would do exhaustive tests and sketches. I wasn't satisfied with some low resolution cartoonish "video art" feel. I needed a level of image resolution that reflected the intensity of the material and that didn't diminish the emotional energy of the scenes. This allegiance to "quality" will get intentionally subverted at times so that if you are running a series of experiments and if you're applying an "Photoshop" filter to B&W or color footage that allows the edges to become vaporized and spread out in mysterious ways or turn to a kind of vapor that’s acceptable - at least you know that you're starting from some point of higher resolution.